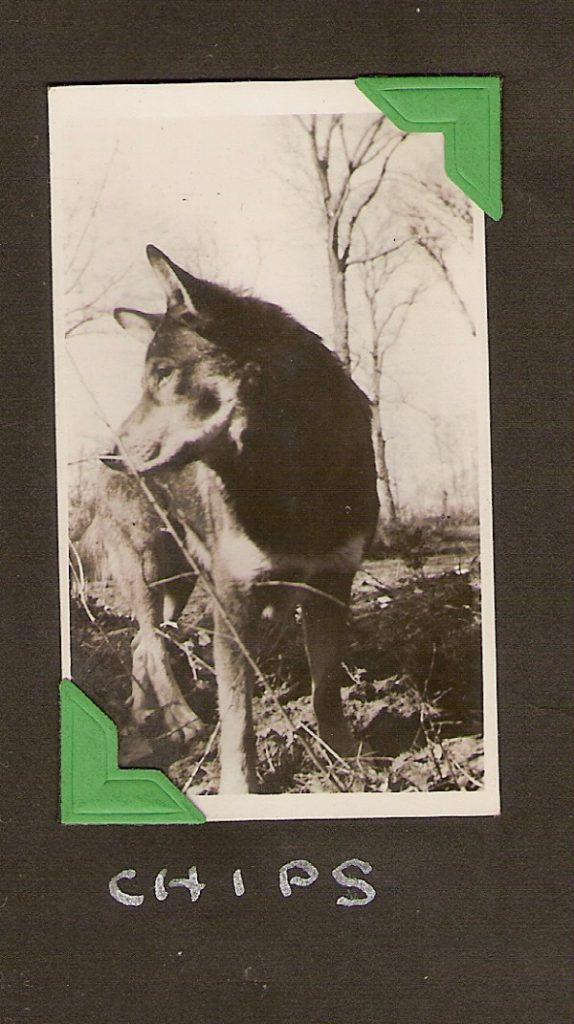

A dog called Chips

by: Mary Ann Whitley

This is a tale of strange coincidences. I work as a copy editor at The Plain Dealer newspaper in Cleveland, Ohio (I edit stories and write headlines). One night at work, I happened to be editing a story that came over the wires that was to be used in our Sunday paper on Aug. 6, 2006. It was about war dogs and the U.S. War Dogs Association’s effort to get medals for these dogs. The story was by Lisa Hoffman of Scripps Howard News Service.

As I read the story, I came upon this paragraph:

In World War II, a shepherd-collie mix named Chips was awarded the Silver Star and Purple Heart for attacking an enemy machine-gun nest in Sicily and, despite a bullet wound, forced the six-man crew to surrender. The Army later revoked the awards, calling it demeaning to service members to give medals to animals.

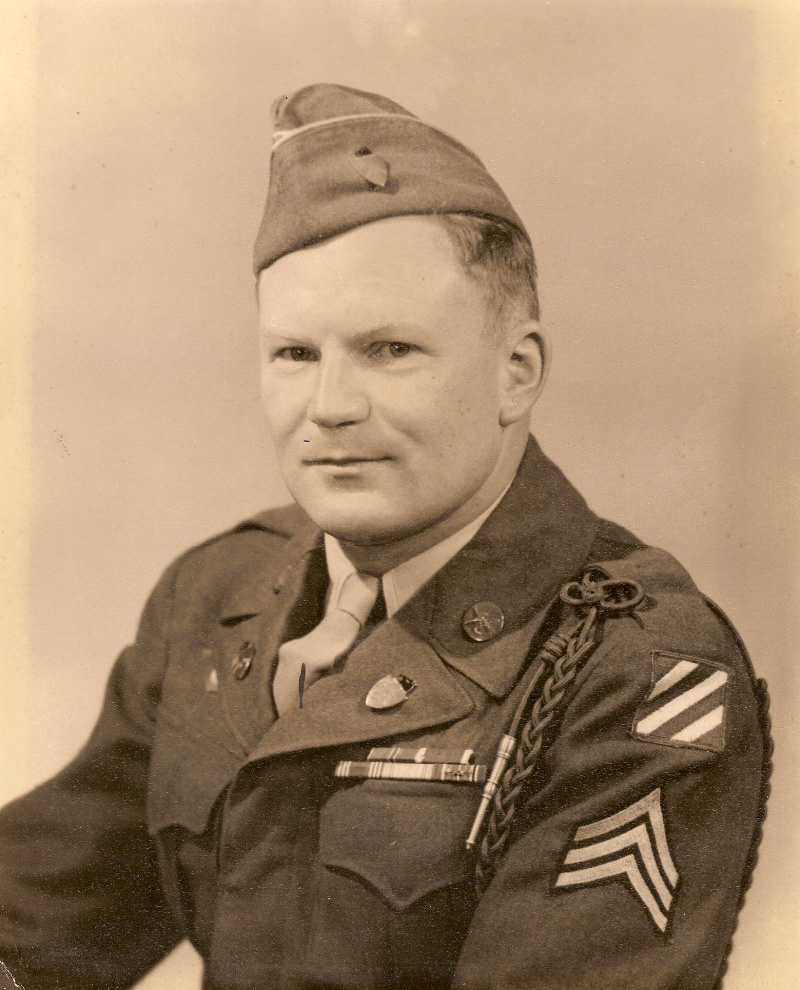

I brought the album in to work the next night and showed it to our national editor. She said that there weren’t any photos of historic war dogs sent with the story, just more modern ones (such as dogs serving in Iraq). So my dad’s old photo of Chips was scanned into the computer system to run with the story in The Plain Dealer. My dad was Sgt. Herson L. Whitley and he died in 1982.

Suddenly, something rang a bell. I was pretty sure I remembered seeing a photo of a dog named Chips in my dad’s photo album. He served with the Third Infantry Division and I knew he had been in Sicily. I looked up Chips on the Web, in the meantime, and a Web site confirmed Chips had been with the Third Division throughout the war, from North Africa, Sicily, Italy, to France and Germany–all places where my dad served. After I got home, I looked through the photo album and sure enough, there was a photo of a dog that my dad had labeled “Chips.” It’s easy to tell it’s the same dog pictured on the Web. I never had any idea who the dog was or why my dad had a photo of him in his album.

It appears that my dad not only had a chance to photograph Chips, but that Chips’ handler must have been serving in very close proximity with my dad. I’d sure like to know more about this … who was Chips’ handler during the war? It’s possible I even have some photos of him among my dad’s pictures, as he labeled some photos on the back with his war buddies’ names. If someone would e-mail me with the name of Chips’ handler, I will be glad to check the photos that I have. (My e-mail address is at the end of this article.)

I then e-mailed Ron Aiello, president of the U.S. War Dogs Association, and told him the story. I offered to share my photo of Chips, so it is here on this page. I’m also including a synopsis of my dad’s wartime service, below. There is also a “p.s.” to this story. After corresponding with Ron, I remembered that I had a large envelope full of my dad’s Army photos–ones that were not in the photo album. I decided to look through them, and lo and behold, I found another photo with Chips. This one had my dad in it and was obviously taken by someone else. Unfortunately, Chips was crossing in front of the camera and the photographer “cut off” his head. On the back of the photo, my dad had written: “Don’t quite know what I’m attempting to do here. Probably trying to get Chips to smile.” I’ve sent the photo and an image of the handwritten note on the back to post here on the USWDA site, as well.

“Don’t quite know what I’m attempting to do here. Probably trying to get Chips to smile.”

Sgt. Herson Lamont Whitley’s service highlights

(From notes taken in a 1970s interview of Herson by his daughter, Mary Ann Whitley, and from his discharge papers)

Herson Whitley served with the Third Infantry Division. He landed in Fedahla, French Morocco, and described the landing this way: It was pitch black. They sent a group ashore. The first ashore were to signal the rest to either attack or land. Herson was standing on the deck of the Leonard Wood waiting his turn to get into a landing boat. He had his rifle belt with ammunition on, three hand grenades and a full field pack, rifle, map case, life belt and was smoking a pipe. He bent over and his pipe fell out of his mouth. He had his hands in his pockets and when he bent over to get the pipe, the life belt expanded and he couldn’t get his hands out of his pockets. Herson often told this story in later years, laughing at the memory of being made helpless by the inflating life belt. During the attack, a piece of shrapnel hit his helmet. He was on guard duty along the Spanish Moroccan border.

In 1942 and 1943, he moved near Algiers for invasion training. He moved up to Tunisia to join Gen. George Patton. The campaign ended in North Africa. The Third Division prepared to invade Sicily; the invasion ended in 40 days. He went to Italy, up to Monte Casino Monastery. The pulled back to make the Anzio invasion. That took six months. He pulled out of Italy to make the southern France invasion. He then served in Germany and Austria until the war ended in 1945.

A family friend later said that Herson was involved in liberating some of the concentration camps. Herson, who was talented at drawing, painting and lettering, also did drafting work during the war, helping to make maps. He recalled meeting Gen. Patton on one occasion when Patton came into the tent where he was working. He said Patton had a high, squeaky voice and wore two pearl-handled pistols.

Herson brought back some interesting “souvenirs” of war. One was an oil painting he said he took from Hitler’s “summer palace,” called the Eagle’s Nest, at Berchtesgaden, Germany, when the war ended. The painting (still owned by his daughter Mary Ann) depicts buildings and trees, is signed by Ernst Friedrich, and was done on something like masonite, rather than canvas. Herson said the painting is of the view looking down from the hilltop retreat. It is not known who the artist is. (Note: Mary Ann has tried numerous times to verify the authenticity of the painting and if anyone has any information that would be helpful, she asks you to email it to her.)

Herson also talked of just missing out on getting Hermann Goering’s personal rifle. He said he saw a locked locker with the initials H.G. on it. [Not sure if this was at Berchtesgaden or elsewhere–M.A. Whitley] He went back out to his Jeep to get something to use to break the lock. When he returned, a higher-ranking officer had the locker open, and had taken possession of the rifle, engraved with Goering’s name. He also brought back some small liqueur glasses from the King of Italy’s palace (Mary Ann still has those as well.) They are engraved with the king’s insignia.

Herson’s honorable discharge papers state that he was wounded with shell fragments in his right hand and leg in Italy on Nov. 15, 1943. He earned the American Defense Service Medal, the Bronze Star Medal, the European-African-Middle Eastern Service Medal with arrowhead, the Good Conduct Medal and the Croix de Guerre with Palm.

Chips Update! (November 2006)

An additional note: My dad was born in Belfast, Ireland (now Northern Ireland), in 1909, and immigrated to the U.S. at the age of 11, settling in Flint, Mich., with his parents and siblings. His unusual first name comes from a friend of the family, Frank Herson. He added the middle name Lamont himself, later in life, taking a family name from his grandmother’s side of the family. Herson’s father (my grandfather) as well as several uncles helped to build the Titanic at the shipyard in Belfast. I spent several years researching that family connection. If interested in learning more about the Titanic, check out the sites for these organizations, of which I’m a member:

www.titanicinternationalsociety.org (Titanic International Society)

www.belfast-titanic.com (Belfast Titanic Society)

— Mary Ann Whitley

E-mail: whitley401@aol.com

Sgt. Herson L. Whitley

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Plain Dealer newspaper article August 6, 2006.