The Dogs of War Laid Their Lives on the Line for U.S.

Los Angeles Times; Los Angeles, Calif.; May 4, 2003; Cecilia Rasmussen

(Copyright The Times Mirror Company; Los Angeles Times 2003. All rights reserved.)

Each had just one name — Jim, Prince, Ruff, Bear.

]

Together they are believed to be the first of hundreds of four- legged soldiers to be trained, and killed, in the line of duty as part of the U.S. Army’s “K-9 Command” program at Ft. MacArthur in San Pedro. For decades they have lain buried, along with two dozen other valiant wartime dogs, behind the base chapel.

These fallen tail-wagging troops were the dogs of war: muscular Doberman pinschers, German shepherds and, for a time, some specially bred canines called GI dogs, trained for sentry duty and attack. “Although the Army used sled dogs as early as 1913 for transportation” and delivering messages and supplies, “Ft. MacArthur is believed to be the first base to use

Sgt Bob Pierce introduces himself to his new training partner “Rin” the grandson of the legendary K9 Actor Rin-Tin-Tin dogs as weapons,” said Steve Nelson, director of the Ft. MacArthur Museum, the centerpiece of Angels Gate Park.

On Sept. 9, 1941, Sgt. Robert H. Pearce put together a “war dog” platoon at Ft. MacArthur. Its original purpose was to “conserve manpower and strengthen the guard by giving sentries an added weapon,” according to the base newsletter. The K-9 Commandos would become progenitors of a new kind of attack dog — bigger, stronger and smarter canine soldiers. Unlike other military dogs of the popular and publicized “Dogs for Defense” program — in which animals were taught to sniff out bombs and land mines, carry battlefield messages and scout trails — the K-9 Commandos’ training to guard and to kill remained pretty much under wraps until the end of the war. Records of their Army service are so spotty that it is uncertain whether they served overseas, and what they might have done there.

The dogs Pearce selected had to be aggressive, physically fit, between 1 and 3 years old, responsive to voice commands, not gun-shy and able to stand their ground without cowering. Many of them were tested and classified by Hollywood dog trainer Carl Spitz, who spent 20 years readying dogs for films and who also trained “Dogs for Defense.” Among his movie-star pupils were Terry, the female Cairn terrier who played Dorothy’s male dog, Toto, in “The Wizard of Oz”; and Buck, one of the dogs used in the film of Jack London’s “The Call of the Wild.”

By January 1942, a month after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, newspaper stories and radio announcements were asking readers and listeners to volunteer their dogs for war duty. Hundreds of Angelenos showed up at Pershing Square, some with cocker spaniels and Boston terriers in tow.

Bruno, a 65-pound chow mix, was the first chosen for the K-9 Command program. Five other recruits, including a schnauzer and a German shepherd named Rin — grandson of dog star Rin-Tin-Tin — were commissioned on the spot, loaded in cages, and taken to Ft. MacArthur for training. One funny-looking dog, clearly not killer material, still found a home at the base. His owner, a San Pedro resident, dropped off the English bulldog at the base with “pedigree papers, fleas and very little ambition,” the base newsletter reported. When he didn’t make the cut, the bulldog was adopted by the Army staff and named Sgt. Mulligan, because he was always getting into the stew — as in Mulligan stew, and that meant trouble. Eventually he became the base mascot.

From their training camp in San Pedro, the dogs were assigned to military bases here and possibly overseas. In 1943, the K-9 Command started a stud service for a new generation of canine gladiators, bred for size, intelligence and ferocity. Major was the biggest of the litter from a German shepherd and American pit bull terrier mix. He was as “tall as a shepherd with a chest as broad as the average man’s,” the base newsletter reported. Major was then bred with an Airedale named Maggie. Their three pups — half Airedale, one-quarter German shepherd and one-quarter American pit bull terrier — were named GI, OD and BC. Soon, they were isolated to ensure that they didn’t pick up the habits of the other dogs, and to prevent Army personnel from petting them. When they were 4 months old, the three began training to respond to voice commands, to run obstacle courses, and to stalk and attack the enemy. After peace came in 1945, the Army’s K-9 Command unit went public. GI, OD and BC, along with another trio, Wolf, Cisco and Rin – – the one with Rin-Tin-Tin as his ancestor — showed off their attack skills for an audience at the Ann Street animal shelter and at the Pan Pacific Auditorium in Los Angeles.

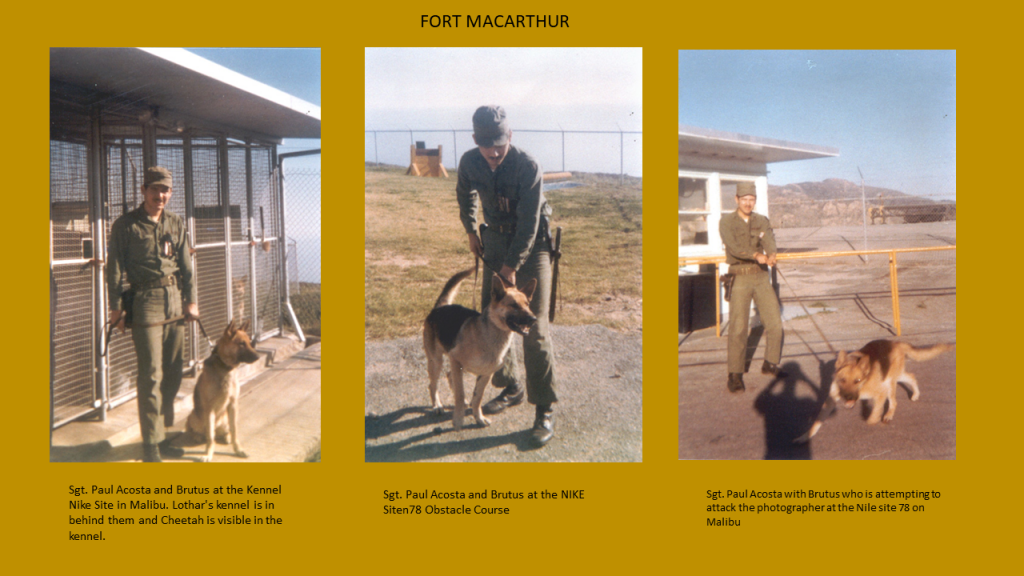

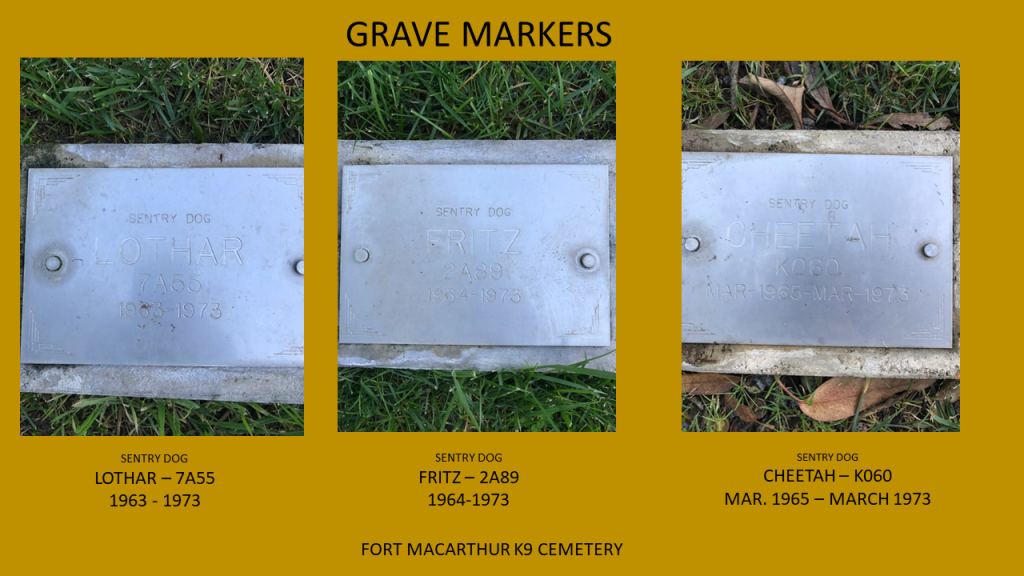

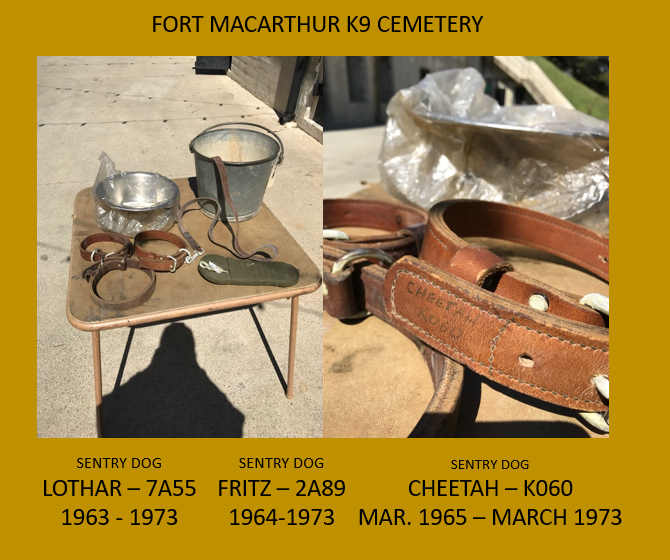

During the Cold War, trained dogs were needed for sentry duty at 16 Nike missile sites that ringed Orange and Los Angeles counties. Ft. MacArthur was the headquarters for the bases. One of the four-footed soldiers was Brutus, a 95-pound German shepherd with his serial number, 737 alpha, tattooed in his ear. Brutus was trained at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio and transferred, along with his handler, Army Pvt. Paul Acosta, to the Malibu Nike missile site in 1970. Their assignment: to guard 18 nuclear warheads.

At the Malibu compound, a guard armed with a .45-caliber handgun was stationed at the entrance to the command and launch areas. Another armed guard and his dog patrolled an inner defensive perimeter. Brutus, Lothar, Cheetah and Fritz were known for their fearlessness, skill at finding trespassers and AWOL soldiers, and ability to discern the good guys from the bad. But life was not all work and no play. “I played practical jokes on the security guards all the time, because the guards were so antagonistic toward Brutus,” Acosta said. “They always threatened to shoot my dog if I ever let him off his leash. So one night I caught an off-duty guard sleeping and put a piece of bologna on his chest. Just to watch his face when he woke up and found Brutus, teeth bared, was worth a million bucks.”

In the mid-1970s, the Nike sites were abandoned and the canines retired, but they would never know civilian life. The dogs were taken to Ft. MacArthur and put to death. A military policy, in effect since 1949, prohibited the dogs’ adoption because they were trained to attack. That policy was rescinded in 2000, after years of campaigning by veterinarian William Putney of Woodland Hills. Acosta testifies to Brutus’ good heart. “Even though these dogs were trained to kill, they were very affectionate with their handlers,” he said. “I could confide in Brutus things I could never tell my wife. “When I got out of the Army,” he said, “I got another German shepherd and named him Brutus.

Sgt. Paul Acosta, B Battery, 4th. Battalion 65th. ADA.

Footnote:

It might also interest you to know that Fort MacArthur is the birth place of US War dogs. While dogs were used in Alaska and Greenland they were for transport a noble service worthy of acknowledgement. That notwithstanding Fort MacArthur actually used their dogs for protecting the fire control equipment for our heavy coast artillery. All of this started a year before Dogs for Defense was started.

Stephen Nelson, Director, Ft. Macarthur Museum.