America with the exception of a few sled dogs in Alaska was the only country to take part in World War I that had no service dogs within its military.

The French, British and Belgians by 1918 had at least 20,000 dogs on the battlefield, the Germans 30,000. But America’s war department felt that now that they were ‘over there,’ the war would be quickly over and there would be no need for any dogs! Even after the General Headquarters of the American Expeditionary Forces, in the spring of 1918, recommended the use of dogs as sentries, massagers and draft animals.

The proposal suggested that 500 dogs be obtained from the French every three months and after training, each of the division be supplied with 288 dogs each.

It also recommended the establishment of training schools in the United States and the construction of five kennels within the battle areas that could house 200 dogs each.

But Washington after ‘reviewing the proposal,’ dropped the suggested plan entirely, firmly believing the war would soon be over. So for the remainder of the war, the American Force had to depend solely on the French and the British for whatever dogs they used.

Sergeant Stubby

America’s first war dog, Stubby, served 18 months ‘over there’ and participated in seventeen battles on the Western Front. He saved his regiment from surprise mustard gas attacks, located and comforted the wounded, and even once caught a German spy by the seat of his pants. Back home his exploits were front page news of every major newspaper.

Stubby was a bull terrier – broadly speaking, very broadly! No one ever discovered where he hailed from originally. One day he just appeared, when a bunch of soldiers were training at Yale Field in New Haven, Ct; he trotted in and out among the ranks as they drilled, stopping to make a friend here and a friend there, until pretty soon he was on chummy terms with the whole bunch.

One soldier though, in particular, developed a fondest for the dog, a Corporal Robert Conroy, who when it became time for the outfit to ship out, hid Stubby on board the troop ship.

So stowaway Stubby sailed for France, after that Cpl. Conroy became his accepted master, even though he was still on chummy terms with everyone else in the outfit; and in the same spirit of camaraderie that had marked his initial overtures at Yale.

It was at Chemin des Dames that Stubby saw his first action, and it was there that the boys discovered he was a war dog par excellence. The boom of artillery fire didn’t faze him in least, and he soon learned to follow the men’s example of ducking when the big ones started falling close. Naturally he didn’t know why he was ducking, but it became a great game to see who could hit the dugout first. After a few days, Stubby won every time. He could hear the whine of shells long before the men. It got so they’d watch him!

Then one night Stubby made doggy history. It was an unusually quiet night in the trenches. Some of the boys were catching cat naps in muddy dugouts, and Stubby was stretched out beside Conroy. Suddenly his big blunt head snapped up and his ears pricked alert. The movement woke Conroy, who looked at the dog sleepily just in time to see him sniff the air tentatively, utter a low growl, then spring to his feet, and go bounding from the dugout, around a corner out of sight.

A few seconds later there was a sharp cry of pain and then the sound of a great scuffle outside. Conroy jumped from his bed, grabbed his rifle and went tearing out towards the direction of the noise.

A ludicrous sight met his eyes. Single-pawed, in a vigorous offensive from the rear, Stubby had captured a German spy, who’d been prowling through the trenches. The man was whirling desperately in an effort to shake off the snarling bundle of canine tooth and muscle that had attached itself to his differential. But Stubby was there to stay.

It took only a few moments to capture the Hun and disarm him, but it required considerably more time to convince Stubby that his mission had been successfully carried out and that he should now release the beautiful hold he had on that nice, soft German bottom.

By the end of the war, Stubby was known not only to every regiment, division, and army, but to the whole AEF. Honors by the bale were heaped on his muscled shoulders. At Mandres en Bassigny he was introduced to President Woodrow Wilson, who “shook hands” with him. Medal and emblemed jackets were bestowed upon him for each deed of valor, plus a wound stripe for his grenade splinter. Not to be left out, the Marines even made him an honorary sergeant.

After the Armistice was signed, Stubby returned home with Conroy and his popularity seemed to grow even more. He became a nationally acclaimed hero, and eventually was received by presidents Harding and Coolidge. Even General John “Black Jack” Pershing, who commanded the American Expeditionary Forces during the war, presented Stubby with a gold medal made by the Humane Society and declared him to be a “hero of the highest caliber.”

Stubby toured the country by invitation and probably led more parades than any other dog in American history; he was also promoted to honorary sergeant by the Legion, becoming the highest ranking dog to ever serve in the Army.

He was even made an honorary member of the American Red Cross, the American Legion and the YMCA, which issued him a lifetime membership card good for “three bones a day and a place to sleep.”

Afterwards, Stubby became Georgetown University’s mascot. In 1921, Stubby’s owner, Robert Conroy was headed to Georgetown for law school and took the dog along. According to a 1983 account in Georgetown Magazine, Stubby “served several terms as mascot to the football team.” Between the halves, Stubby would nudge a football around the field, much to the delight of the crowd.

Old age finally caught up with the small warrior on April 4th, 1926, as he took ill and died in Conroy’s arms.

It’s said, that Stubby and a few of his friends were instrumental in inspiring the creation of the United States ‘K-9 Corps’ just in time for World War ll.

Hahn’s 50th AP K-9, West Germany

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

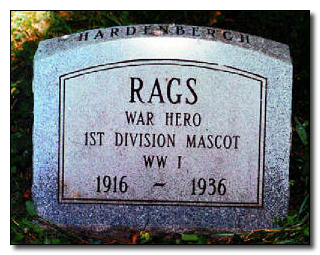

Rags (c. 1916 – March 6, 1936)] was a mixed breed terrier who became the U.S. 1st Infantry Division’s dog-mascot in World War I.

He was adopted into the 1st Division on July 14, 1918, in the Montmartre section of Paris, France. Rags remained its mascot until his death in Washington, D.C. on March 22, 1936. He learned to run messages between the rear headquarters and the front lines, and provided early warning of incoming shells. Rags achieved great notoriety and celebrity war dog fame when he saved many lives in the Meuse-Argonne Campaign by delivering a vital message despite being bombed, gassed and partially blinded. His adopted owner and handler, Private James Donovan, was seriously wounded and gassed, dying after returning to a military hospital at Fort Sheridan in Chicago. Rags was adopted by the family of Major Raymond W. Hardenbergh there in 1920, moving with them through several transfers until in Fort Hamilton, New York, he was reunited with members of the 18th Infantry Regiment who had known him in France. Rags was presented with a number of medals and awards.

Rags was found abandoned on the streets of Paris by an American doughboy, Private James Donovan, an A.E.F. signal corps specialist serving with the U.S. 1st Infantry Division. Donovan named the dog Rags because when he first found him he mistook him for a pile of rags. Donovan had marched in the Bastille Day parade and was late in reporting back to his unit. To avoid being Absent Without Leave, Donovan told Military Police that Rags was the missing mascot of the 1st Infantry Division and that he was part of a search party. That is a role that Rags was to play for almost twenty years. Upon returning to his unit Donovan escaped punishment and was allowed to keep Rags largely because Donovan was being ordered to the front lines.

War service

Donovan’s job in the front lines was to string communications wire between advancing infantry and supporting field artillery. He also had to repair field telephone wires that had been damaged by shellfire. Until wire was replaced, runners had to be used, but they were frequently wounded, killed or could not get through shell holes and barbed wire. Donovan trained Rags to carry written messages attached to his collar.

In July 1918, Rags and Donovan and an infantry unit of 42 men were cut off and surrounded by Germans. Rags carried back a message which resulted in an artillery barrage and reinforcements that rescued the group. News of the exploit spread throughout the 1st Division.

In September 1918, Rags and Donovan were involved in the final American campaign of the war. Rags carried a number of messages and on October 2, 1918, carried one from the 1st Battalion of the 26th Infantry Regiment to the 7th Field Artillery that resulted in an artillery barrage that led to an important objective, the Very-Epinonville Road, being secured. It saved the lives of a large number of doughboys].

On October 9, 1918, Rags and Donovan were both the victims of German shellfire and gas shells. Rags had his right front paw, right ear and right eye damaged by shell splinters, and was also mildly gassed. Donovan was more seriously wounded and badly gassed. The two were kept together and taken back to a dressing station and then several different hospitals. Whenever this unusual treatment for a mere dog was mentioned, the term “orders from headquarters” was brought into play. Rags’ reputation helped smooth the way. The dog quickly healed after excellent treatment. Donovan’s health, however, grew worse. Both were returned to the United States.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia