God, My Dog and I

-by Harold “Al” Tesch, CPL USMC

Third War Dog Platoon

Guadalcanal, Guam, Iwo Jima

(subject interview April, 1977)

Our three kids all grew up around dogs. Dogs and more dogs — Ruth and I had ’em, for sure. But there never was another dog like Tippy. In my heart I will always believe that God sent Tippy to protect me. Which he did, many times over. Trouble is, I don’t know why. Don’t we all seek explanations for things that happen in our lives? But I stopped asking myself the reason a long time ago. I was just torturing myself. I know now there is no answer. Not in this life, anyway.

Yes, you can say I tolerate dogs and then some. As a youngster I worked for a vet after school. Dogs came natural to me. I was born in Penfield, in upstate New York, near Lake Ontario. My folks moved 21 times before I was 18. But that happened a lot in those hard times.

In early 1943 I quit Brighton High and joined the Marines. With my background I went straight from boot camp to the Third War Dog Platoon, Camp Lejuene. There were two platoons, the Second and Third. Dogs from all over the country were shipped there. Mostly problem animals, maybe a hundred in all to start with. Dobermans and German Shepherds, mostly. And one malamute. That sled dog wanted everybody’s hide — step right up! He’d gotten loose and chewed half-a-dozen Marines. And he didn’t monkey around — a flying leap straight for the throat. I’ll tell you how tough that dog was. The U.S. Army had him first, but they labeled him incorrigible and shipped him off to the Marines with a lot of other trouble-makers. If there had been a brig for dogs at Lejuene, I believe Tippy would have spent the entire war in solitary confinement on bread and water.

The first time I saw him he was leashed to his kennel. I walked up to him, not knowing anything at all about his behavior. He just stood there looking at me. OK. Then he jumps up and puts his front feet on my stomach, and his bushy tail’s a-waggin’. Hey, what a nice doggie! Pretty soon a crowd gathered, waiting to see me turned into kibbles. So that’s how it happened. The dog picked me — I didn’t pick him. Now that’s the first “why?” But not the last– not the last that I have no answer for. Do you follow what I’m saying?

Every dog required two handlers, in case one got hit in combat. So far as I know I was the only dog handler in the Marine Corps without a partner. They made an exception in my case. For a very long time the dog wouldn’t let anybody else come close. So in the beginning I really had to plead my case, and they finally consented on a trial basis. And a good thing, because when it got down to the nitty-gritty of training, with all the grenades and gunfire, a few of the dogs went crazy and had to be destroyed. But not old Tipper. He took it all in stride — obstacle courses, rifle fire, machine guns, mortars, dynamite satchel charges — nothing fazed him. He came by his name because his left ear, when he was relaxed, tipped down and forward at a right angle. And that droopy ear saved more than one Marine’s life, I can honestly say — and cost the enemy dearly.

“Corporal Al Tesch, USMC and his sidekick

Sargeant Tippy take a break on Guadalcanal, 1943.

The pair normally scouted ahead of platoon-strength

patrols, probing for Japanese strong points.”

OK, so where did this dog come from? For that we go to a tavern on the northside of Chicago. Vic’s Place. Owned by a gentleman named Victor Lunardini. Vic had been broken into a couple times, so he got this dog from the city pound and left it inside the tavern every night. During the day the dog was kept locked in the office, but the growls and snarls every time a customer walked by on his

“way to the john made for nervous clientele — and Vic soon heard of it. He worried that the dog might accidentally get loose and chew on somebody. That’s when he decided to return it to the city pound where it would undoubtedly be put away.

Next, we need to meet Vic’s 12-year-old daughter, Hazel. She’s the reason I’m sitting here talking to you now. Hazel showed her father a newspaper clipping from the Chicago Tribune. The story told about how the War Department needed dogs with bad tempers. So Mr. Lunardini shipped the dog off to the Army. That made Hazel a happy little girl. And set my life on a course that I never could have dreamed of.

So we finished our training. Tippy was now officially a scout dog. I taught him hand and voice signals, and also how to respond to muscle flexes. When we stopped, he automatically leaned against my right leg to make contact, and then waited for any twitches. And I had to learn to read the dog’s signals, what they meant, but most of that came later in combat.

We went to Guadalcanal on a ransport, the dogs in cages stacked all over the quarter deck. They got exercised every day. The Marine division we relieved went to Australia or Hawaii, I can’t recall which, and our job was to help the Army clean up the island. We snooped around in caves and dugouts looking for stragglers, but most of them by now were starving and pretty helpless. The closest I came to getting it was on a night patrol. Tippy stopped cold and wouldn’t take another step. I kept coaxing him but he wouldn’t move. So the bunch of us went back maybe fifty feet to a clearing and bivouacked for the night. At first light the squad leader woke me up with a huge grin on his face and practically dragged me to the spot. He didn’t say a word, just pointed. About six feet from where Tippy stopped, was a drop-off. Straight down maybe 150 feet to a pile of boulders. Tippy got a belly full of K-rations for that caper.

After five months on the Canal, the Third Division took part in the Guam invasion. By nightfall of the first day we’d worked inland about 250 yards to a coral ridge. I’m flat on my back star-gazing and a mortar round lands two feet away from the dog. Up and over he goes and naturally my arm comes right out of its socket because the dog is secured to a hand leash.

So Tippy’s yelping and yipping and can’t move his hindquarters and I’ve got coral fragments and shrapnel in my left side and I’m hollering “Corpsman!” Suddenly the corpsman runs up and kneels down and Tippy sinks his teeth into the guy’s arm. I’m talking 700 pounds pressure to the square inch. So now there’s three patients instead of two.

I went to the field hospital to get my wounds cleaned out, and then I signed a paper that said I was returning unfit for duty at my own request. I found Tippy still recovering from a nasty concussion. For a week I mixed APC tablets with his food. Otherwise, he didn’t have a scratch. But two guys twenty feet away from us were both killed by that mortar round.

It didn’t take long before we had our routine down to a science. Not an art. A science. The dog takes the point, scouting ahead. He’s off the leash. Me right behind, then the backup. His left ear would come up and then they’d both perk. We called it “alerting.” So his pointed ears would perk like that, and then his head would bob up and down trying to locate the scent. Now if he was really hot, his hair would bristle and heíd give a low growl. No! more like a rumble. Tippy never barked, and he never gave a false alert. Not once, not ever.

So what I’d do is crouch down low and put my head directly behind his. Then I’d take a line of sight and look down the top of his muzzle as if I were aiming a rifle barrel. I used to think of his ears as rear sights, just like those on a twenty-two I owned as a kid. And invariably that would be where the enemy was. In-variably.

But I had to learn the hard way. One time the dog alerted on a palm tree. Two men from another platoon had been sniped early that morning and everybody was jittery. I lined up and when I saw what Tippy was looking at, I knew he was goofing off because nobody was in that tree. I could plainly see that. But I figured what the heck, and starting firing my carbine and then everybody opened up. The entire tree top just leaned over and down against the trunk. So we walked over and started pulling and poking and here’s this sniper hanging there all cloaked with palm fronds — a really skillful camouflage job. Think about it. A deer can’t scent a hunter in a tree stand. No way. But Tippy knew.

Another time we came on a hut and thinking there were natives inside, I walked up and gave a loud holler. Hello! mailman! Anybody home? The door flies open. On a dead run and swinging his sabre is this Japanese officer, about six-foot-five. Which is a lot taller than me or anybody that’s backing me up. He’s got this really handsome Van Dyke beard, which came as a complete surprise to me and totally threw me off-guard. He covered fifteen feet of ground in three bounds before I finally came to my senses.

Afterwards, I’m still shaking and upset with myself. I look around and no Tippy. So I strolled behind the hut and he’s got four or five more people pinned down in the saw grass. I believe the dog owes his life to the fact the enemy didn’t want us to know they were hiding back there, planning an ambush. Otherwise, they would have shot him. So we were both lucky that day.

My worst encounter on Guam, meaning it’s one I feel remorse about, happened in a strange way. By this time, the Seabees had put up a number of buildings and the officers began hiring natives to clean up their quarters and mess hall and do odd jobs. Late one afternoon I was detailed to escort a young Guamanian girl back to her house about a half-mile away. I took Tippy along for the walk. The minute we stepped inside the hut, the dog alerted. I asked a few questions but couldn’t get any straight answers. I didn’t think much about it at the time, but the next morning the hairs on my neck started tingling. It suddenly came to me that the girl, who wasn’t much older than I was, had carelessly — or maybe even deliberately — put me in harms way. And the more I entertained the notion, the madder I got. I mean, my blood was up. I simply had to know. So I decided to wait about a week when there would be a full moon.

On that night I had no way of judging the time, but the moon was over the treetops so I’d say sometime after midnite. I was hidden on a steep hillside and I was getting antzy. I could see a dim lantern light through one of the hut’s open windows. The first clue came when I felt Tippy’s shoulder muscles tighten against my calf. Then his hair bristled and a low rumble sounded in his chest. I clamped the fingers of both hands around his throat, then gradually increased my grip until he fell silent. After what seemed like an hour, two figures stepped out of the brush onto the open path leading to the hut. Both were carrying slung rifles, that much I could tell. They stood there awhile listening and then went up the stairs into the hut.

I took Tippy’s leash and snapped it on his collar and tied the other end to a tree. I came down the hillside and stood in the shadows. I kept trying to remember if the porch steps squeaked or not. Just to be safe, I went around to one end and slid under the railing and then crawled along the porch under the window. When I got to the door I stood up and kicked it open. And, uh — that was it. No questions asked.

After things quieted down, we got some recreation. Tippy loved to shag balls. One day we staged an exhibition ball game. The big attractions were PeeWee Reese and Ted Williams. Williams was a Marine Corsair pilot. I was playing shortstop. Williams slams one — it’s a homer. And just about the time Williams is rounding second base here comes old Tipper tearing across the outfield and he drops the ball at my feet. Everybody’s cheering and whistling as Williams touches home plate. And I think to this day that Mr. Red Sox never knew the applause wasn’t for him.

We finally got orders in late forty-four to move out, and that meant a field inspection. Major General Erskine, our division commander, headed the inspection party. He walked up and down the front ranks of our battalion, loudly praising the devil dogs. That’s when Tippy bit him. Guys up and down the line later told me they could hear khaki rippin’ and then flappin’ in the wind like Old Glory. I didn’t hear a thing — I was scared stiff.

I know I’m gonna be court-martialed. I didn’t have Tippy’s leash short-snubbed. Then the General says in a loud voice: “Gentlemen, we have just witnessed a classic example of what these splendid canines are trained to do — ATTACK!” And off he goes, and that’s the first and last word I ever hear on the subject.

Next stop, Iwo Jima. It just kept getting worse and worse. We were almost to the first airfield and at that point nobody had slept for around sixty hours, except maybe on his feet. A group of us settled in for the night, and of course I always had to dig a bigger foxhole so Tippy had some protection. When I came to in the morning there was nothing but corpses and body parts strewn around. I found out later they’d dropped a mortar barrage right on top of us, and followed that up with a close-in grenade attack. But I never heard a thing. Most of the dead must’ve been killed in their sleep.

When I realized I was the only survivor, I thought God had got his signals crossed. So I got out my pocket bible and that’s when I came across this verse that stopped me in my tracks, and which I will now repeat. “I am caught in this dilemma. I want to be gone and be with Christ, which would be very much better. But for me to stay alive in this body is a more urgent need for your sake. This weighs with me so much that I feel I shall survive and stay with you, and help you to progress in the faith and even increase your joy in it.” I read the verse a dozen times or more, so that the words filled my heart and mind. They seemed to flow out of me as if they were my own. And by the end of the day I came to accept that my deliverance was more than just an accident. I vowed then and there to do everything I could to stay alive and return home. Not many days after, the parasites in my gut and a recurring case of dengue fever combined to send me back to Guam, to the hospital. I was the first serviceman in the Pacific theater to receive blood plasma, instead of whole blood, and this helped pull me through. Then finally the war was over. Two weeks later I was told I had thirty minutes to pack my gear. Well, that was easy. I only needed five. I was going home. But I panicked because Tippy and the other surviving dogs were on the far side of the island and there was no way to get word to anyone in the platoon. That same night a group of Japanese infiltrated the hospital compound and killed most everybody, spearing and hacking helpless patients and staff alike, but I didn’t know about it for thirty years. My buddies on the island assumed I’d been killed.

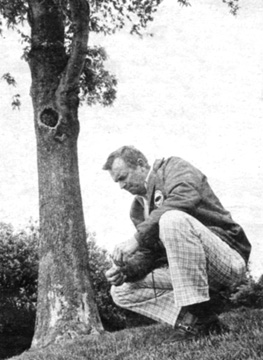

“In 1949, Al Tesch buried his beloved companion

beside this hickory tree on what was once the

family farm, and now a residential backyard

outside Henrietta, N.Y. This visit by Al in

1977 was one of many over the years.”

So now I’m back in Brighton and living on the family farm. But nothing happens. No revelation. Where is the “urgent need” that requires my attention? Who had I helped to “progress in the faith”? I go to work for a dairy farmer in Henrietta. Then I work raising cash crops. Then building and remodeling houses. Then in June of forty-six I get married to Ruth. We spend our honeymoon in the beautiful downtown Rochester Hotel, overlooking Main and Plymouth. In the middle of the night the radiator blew off steam and I dragged Ruthie under the bed. Half our blissful weekend I devote to throwing up because of the bugs in my gut. I was very talented at throwing up in those days. In fact, I became an expert marksman all over again.

We’d just settled down to married life for about a month when I was notified of a freight shipment at the Rochester depot. Waiting for me was a beaten, battered old crate that had traveled half the globe. I don’t have to tell you what was inside. I let the dog out and I swear he must have peed for five minutes. Then he danced and leaped around for five minutes more. That’s a Marine for you. Tippy held his water all the way from North Carolina to New York. For all I know, maybe standing at attention.

It took me a while to track down what happened. Most of the dogs were on loan, like lend-lease. After the war all but a few were deprogrammed, or detrained, then returned to their owners. Tippy’s owner was listed as Hazel Lunardini. We wrote each other while I was overseas, but she never told me she had leukemia. And unbeknownst to me, just before she died, she wrote directly to the commandant of the Corps, General Vandergrift, and asked that her dog, Sergeant Tippy, be placed in the permanent care and keeping of her friend and pen pal, Corporal Al Tesch.

So now it was me, Ruth and Tippy down on the farm. My wife was uneasy at first, but Tippy won her over when Ruth came down with the flu. The dog stayed at her bedside the entire week she was sick. And I’ll never forget the evening we were doing the dishes. I gave Ruthie a playful pat on the behind. Well, she let out a yelp, and the next thing I knew Tippy was at my feet, looking me straight in the eye and growling that familiar rumble. And I said hey buster, you trying to break up my marriage?

I went back to building houses and Tippy went with me every day. I was doing a roof once and who comes climbing over the top of the ladder, two stories up. Just another obstacle course to overcome. Of course I had to carry him down. We even went pheasant hunting together. Have you ever seen a malamute on point? Of course not, and you never will. But I did. And Tipper had a gentle mouth, which surprised me no end after all his crunching and munching. He never left a toothmark in any of those cockbirds. A grand time, and no return fire.

But I still had my problems. So I went to see this minister, the Reverend Albert D’Annunzio, the same one who’d married us. Heís retired now. I helped him build his first church. And I told him that I believed God had spared my life to be His witness, but that I’d failed. I was a failure. We had a very long talk, and the Reverend said he’d give what I had to say some long and serious thought and get back to me.

And so the first thing I know I’m up in his pulpit on a Sunday morning. Me and Tippy. I told about our war experiences, about reading the scripture at the side of my foxhole. And about our separation and what seemed to me a miraculous reunion. Afterwards, Tippy performed for the congregation right there in church.

We did that for two summers, going to Christian youth rallies all over western New York. I put together a little talk. God, My Dog, and I. Reverend D’Annunzio helped out on stage, and Tippy did his bagful of tricks. And the young people flocked around, I’ll tell you.

“Fellow Marines keep a wary eye on Tippy as

they prepare to bed down for the night in a

captured Japanese dugout on Guam.”

And then the word got out and we started going to state prisons. One time at Auburn, I was sitting on the stage and Tippy was on his haunches leaning against my leg. An inmate in the front row stood up and shouted hey! — that damn dog is nothing but a sissy. He wouldn’t scratch his own fleas. So I said sir, would you mind raising your right arm? Which he does. And I flex my calf muscle —

nothing else – and Tipper comes flying off the stage and lands right at this guy’s feet. And I holler DON’T MOVE! And he’s standing there holding his arm up in the air, and I said OK, you have Tippy’s permission to go to the bathroom. And I think the guy already did. You can’t imagine the stomping and hollering. I thought I was in the middle of a prison riot.

A few minutes later I coaxed this same guy up on the stage to help me hold a broomstick for Tippy’s balancing act. When that was over, Tippy grabbed one end of the stick in his mouth and I grabbed the other end and around and around we went in a chest-high circle. Then Tippy let go and dropped to his stomach facing me, while I faced the audience. I rolled my wide-open eyes to the left. Tippy did a belly crawl to the left. Same to the right. Then we got into some serious math. Tippy moved pieces of wood around, solving addition and subtraction problems that I posed to him. Believe it or not, I still get letters from some of these men. Maybe they’re up for parole and need references, or a job. They still remember Tippy after all these years.

Tippy, handsome devil that he was, had his share of lady friends. I didn’t think much of it when he didn’t make it home on occasion. September 14, 1949 was one of those times. But after two days I got worried and went out looking. I found Tipper in a ditch up the highway. I could see the tire tracks in the grass. The driver had to dodge two phone poles to run him down. In military terms he was ambushed.

Harold “Al” Tesch

Branch of Service: USMC

Unit: 3rd. War Dog Platoon

Dates: 1943-1945

Location: Pacific Theater

Rank: CPL

Birth Year: 1925

Entered Service: Penfield, NY